Three recent pieces of research really move on our understanding, taking the lengthy investigation in an unexpected direction and turning the spotlight on social care provision.

22 May 2017

Since the 1960s, public health research has suggested that differences in lifestyles (smoking, drinking, diet and exercise) explain much of the variation in postcode longevity. Of course, these statistics are merely saying that the habits of people living in certain areas are associated with low or high life expectancy, and don’t prove beyond reasonable doubt that the habits are necessarily causing the variation in life expectancy.

In addition to lifestyle, I have long wondered how big an effect the genes we inherit from our parents could have on our longevity. In other words, how much of a helping hand did the genetic lottery bestow on the long-lived?

1. Your genes at birth have little impact on your longevity

Exhibit one comes from the advancing frontier of genetic research, where microbiology meets mathematics. The technology revolution that has turned the sequencing of the human genome into an everyday industrial process is revealing previously untold secrets. By looking at how longevity runs in families, geneticists have long believed that a small part could be attributed to genes, the rest being due to lifestyle and ever-present chance, but only now are researchers beginning to pinpoint which genes matter. The research of actuary-turned-geneticist Dr Peter Joshi at Edinburgh University is showing that inherited faulty genes already linked to a small number of nasty diseases like lung cancer, are affecting lifespans, but as yet do not explain all the genetic differences in longevity between different people within the same community. At the same time, he has also shown that genetic variants that increase educational levels also increase lifespan. Here's a taster of Peter's work.

My take-away – as someone modelling longevity for portfolios of pensioners - is that a higher proportion of the variations in longevity outcomes are now known to come from things that happened after birth than was previously believed. That takes us to the second fascinating nugget, again coming from the exciting new world of genomics.

2. The accumulating damage to your genome is greater for those with unhealthy lifestyles

Exhibit two comes from a new book about how things called "telomeres" in our DNA affect the speed of our body clocks. It suggests that the pace at which our DNA ages as we live our lives – the biological “rusting” of our bodies as cells renew – is related to the healthiness of our habits. The suggestion is that those who look after their bodies with the same tender care as the owner of a priceless vintage car can slow down their ageing process.

This may not come as a shock, but association is now turning into causation, with the fundamental research on the genome explaining past public health observations. When combined with the news that the genes we are born with have little influence on lifespan, I feel like a nagging doubt has been removed. I feel more in control of my own destiny and it gives me more motivation to invest time in staying healthy.

3. Is the social care crisis now affecting death rates?

Exhibit three follows from Club Vita research that your pension fund records have enabled. The previous edition of VitaMins longevity turbulence revealed the sharp “dislocation” between longevity trends (the rate of fall in death rates) when pensioners with defined benefit pension schemes are put into three broad socio-economic groupings. During the noughties decade, we observed faster falls in death rates in Hard Pressed and Making-Do pensioner groups than the Comfortable. But this ranking was reversed in 2010-2015, with slower increases for Hard Pressed and Making-Do.

Explaining this finding is causing much head scratching. The patterns in 2000-2010 were consistent with a social cascade effect, with the less affluent benefiting from improving lifestyles, probably adopted some years earlier. But the closing of the longevity gap came to an abrupt end. That suggests something happened in the current environment rather than an accumulation of things from the past.

The initial theories for the rise in population death rates were a severe winter and an ineffective flu vaccine. This research from 2020 Delivery has largely eliminated these theories. With continued heavier death rates in the national population, attention is now turning to the capacity in the UK health and social care systems, what the Sun newspaper pithily summed up as “Austerity Kills”.

Given the universal health care of the NHS, how can the Club Vita findings be reconciled? We wonder whether the pressures on our means-tested social care system are having an effect. The squeeze on local authority funding has caused many care homes to close, despite the growing demand from an ageing population. Could the dislocation be explained by those in the Comfortable group paying their own care home costs, so starting to get around-the-clock care sooner (when they are fitter)?

Circumstantial support for this theory comes from research by the London School of Economics before the financial crisis, which showed that “self-funders” had longer average stays, suggesting that even in those days self-funders where admitted in a healthier state than those paid for by the state (see table 17 of the linked document). We understand that delivering care in the person’s own home is a relatively new option to be offered by local authorities (and is popular with many people). This research would benefit from being updated to reflect today’s model for delivering care.

So, the shape of the numbers fits the description, but the theory is unproven and the search for answers goes on. We would love to hear any alternative suggestions. We appreciate that the provision of good quality care for the elderly is of great interest to Club Vita supporters. We’re hoping to do some more investigating with the help of some of our local government friends, to enable us an evidence-based contribution to the Government’s planned green paper on social care in the autumn.

One size does not fit all

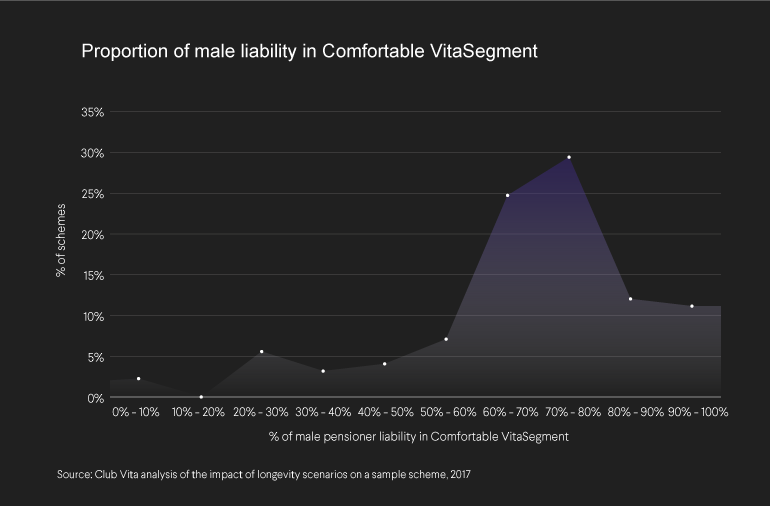

All three of these areas of research illustrate why stratifying populations along socio-economic lines is the sensible thing to do when managing the funding of diverse portfolios of pension liabilities. Within the Club Vita family of 200+ schemes, the average scheme has 70% of its liabilities in the Comfortable group, but there is a wide range from close to zero to almost 100%. Movements in the national population average are simply not representative of what’s going on in the liabilities of our nation’s pension schemes, creating additional business risk.

Find out more

Find out how our unparalleled insights can benefit your fund